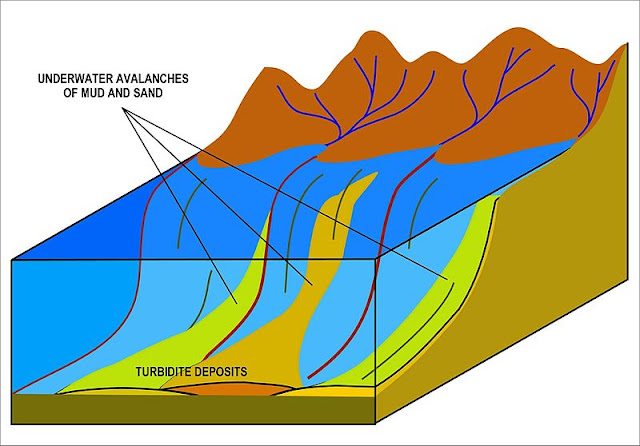

As near as I can tell in the original daily series in 2014,I never addressed the topic of turbidity currents and their sedimentaryproduct, turbidites. But they account for the distribution of vast quantitiesof sediment on continental shelves and slopes and elsewhere.

You know what turbid water is: water with a lot of suspendedsediment, usually fine mud particles. In natural submarine environments,unconsolidated sediment contains a lot of water, and when a slurry-like packageof sediment liquifies, it can flow down slopes under gravity, sometimes forhundreds of kilometers.

It isn’t correct to think of these streams of water andsediment as like rivers on the sea floor. Rivers transport sediment, whetherboulders or sand or silt or mud, through the traction, the friction of themoving water. Turbidity flows are density flows, moving because the density ofthe water-sediment package is greater than the surrounding water. That meansthey can carry larger particles than usual.

Turbidite formation. Image by Oggmus, used under Creative Commons license - source

Turbidite formation. Image by Oggmus, used under Creative Commons license - source

Sometimes a turbidity flow is triggered by something like anearthquake, but they can also start simply because the material reaches athreshold above which gravity takes over and the material flows down slope. Theamount and size of sediment the flow can carry depends on its speed, so as theflow diminishes and wanes, first the coarse, heavier particles settle out,followed by finer and finer sediments. This results in a sediment packagecharacterized by graded bedding – the grain size grades from coarse, withgrains measuring several centimeters or more, to sand, 2 millimeters andsmaller, to silt and finally to mud in the upper part of the package. Repeatedturbidity flows create repeated sequences of graded bedding, and they can addup to many thousands of meters of total sedimentary rock, called turbidites.

Other sedimentary structures in turbidites can includeripple marks, the result of the flow over an earlier sediment surface, as wellas sole marks, which are essentially gouges in the older finer-grained top of aturbidite package by the newest, coarser grains and pebbles moving across it.

There are variations, of course, but the standard package ofsediment sizes and structures, dominated by the graded bedding, is called aBauma Sequence for Arnold Bouma, the sedimentologist who described them in the1960s.

Turbidity currents are pretty common on the edges ofcontinental shelves where the sea floor begins to steepen into the continentalslope, and repeated turbidity flows can carve steep canyons in the shelf andslope. Where the flow bursts out onto the flatter abyssal sea floor, hugevolumes of sediment can accumulate, especially beyond the mouths of the greatrivers of the world which carry lots of sediment.

When the flow is no longer constrained by a canyon or even amore gentle flow surface, the slurry tends to fan out – and the deposits arecalled deep abyssal ocean fans. They are often even shaped like a wide fan,with various branching channels distributing the sediment around the arms ofthe fan. The largest on earth today is the Bengal Fan, offshore from the mouthsof the Ganges and Brahmaputra Rivers in India and Bangladesh. It’s about 3,000km long, 1400 km wide, and more than 16 km, more than 10 miles, thick at itsthickest. It’s the consequence of the collision between India and Eurasia andthe uplift and erosion of the Himalaya.

The scientific value of turbidites includes a record oftectonic uplift, and even seismicity given that often turbidity currents aretriggered by earthquakes. They also have economic value. Within the sequence offining-upward sediments, some portions are typically very well-sorted, cleansandstones. That means they have grains of uniform size and shape and not muchother stuff to gum up the pores between the sand grains – so that makes thempotentially very good reservoirs for oil and natural gas. You need the properarrangements of source rocks, trapping mechanisms, and burial history too, butdeep-water turbidites are explored for specifically, and with success, in theGulf of Mexico, North Sea, offshore Brazil and West Africa, and elsewhere. TheMarlim fields offshore Brazil contained more than 4 billion barrels ofproducible oil reserves when they were discovered in the 1980s.

Ancientturbidites sometimes serve as the host rocks for major gold deposits, such asthose at Bendigo and Ballarat Australia, which are among the top ten goldproducers on earth.

—Richard I. Gibson

Join Podchaser to...

- Rate podcasts and episodes

- Follow podcasts and creators

- Create podcast and episode lists

- & much more

Episode Tags

Claim and edit this page to your liking.

Unlock more with Podchaser Pro

- Audience Insights

- Contact Information

- Demographics

- Charts

- Sponsor History

- and More!

- Account

- Register

- Log In

- Find Friends

- Resources

- Help Center

- Blog

- API

Podchaser is the ultimate destination for podcast data, search, and discovery. Learn More

- © 2024 Podchaser, Inc.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Contact Us