What is dynamic topography? Well, it depends on who you ask. Dynamic topography is similar to other terms, like uplift, that have been used in so many different ways that you really have to look at the document you’re reading to understand what the author is talking about. This term has been applied to places around the world, like the Colorado Plateau in the United States, South Africa, the Aegean, and East Asia, which makes it even more complicated to tease out its meaning.

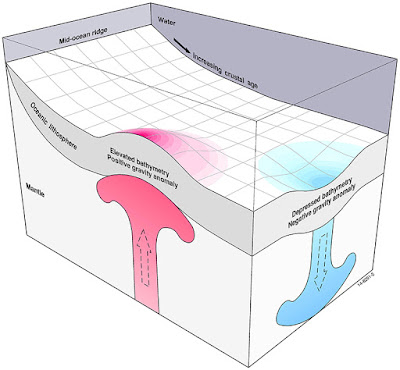

Most broadly, dynamic topography refers to a change in the elevation of the surface of the earth in response to something going on in the mantle. This “something” can include both the flow of the mantle, as well as differences in mantle temperature or density. For the purposes of this podcast, I will use a more strict definition: Dynamic topography is the change in the elevation of the surface of the earth in response to the upward or downward flow of the mantle.

How much higher or lower can dynamic topography make the earth’s surface? Well, that’s a matter of debate. Earlier studies have suggested that several kilometers, or over 6000 feet of modern elevations can be explained by things going on in the mantle. More recent work instead suggests that dynamic topography creates changes of at most a three hundred meters, or a thousand feet.

A good example of a place where this process is thought to be active is Yellowstone. As Dick Gibson discussed in the December 19th, 2014 episode, Yellowstone is thought to be a hot spot. That is, an area of the earth where hot material moves from deep within the mantle to the base of the crust, causing significant volcanism at the surface of the earth. Other well-known hot spots are located in Hawaii, and Iceland.

So how can a hot spot like Yellowstone cause dynamic topography? Well, you’ve probably seen a similar process at play the last time you played in a pool or a lake. Think of the surface of the pool like the surface of the earth. If you start moving your hands up and down under water, the surface of the pool starts to move up and down. If you ever tried to shoot a water gun upwards underwater when you were a kid, you probably remember it pushing up the surface of the water, and being disappointed that it didn’t shoot out at your friend or sibling. As an adult, you could try holding a hose upwards in a pool. Again, it probably won’t shoot out, but will gently push upwards on the surface of the pool.

Dynamic topography concept. © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia)

Dynamic topography concept. © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia)2017, used under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence The principle for a hot spot creating dynamic topography is the same. The flow of the mantle pushes upwards, warping the crust and increasing the elevation of the earth’s surface above the hot spot. Near Yellowstone, this results in an area of high elevation which lies next to the Snake River plain.

But Dynamic Topography doesn’t just cause increases in elevation, it can also pull the earth’s surface downward. In North America, dynamic topography is thought to have been in part responsible for the creation of the Cretaceous interior seaway.

As a reminder, the Cretaceous interior seaway was a shallow sea that covered parts of western North America, in middle to late Cretaceous time, about 100 to 79 million years ago. Its size varied, but at its greatest extent the seaway stretched through Texas and Wyoming in the US, and Alberta and to the Northwest Territories in Canada. It was widest near the US-Canadian border, where it stretched from Montana to western Minnesota.

Low elevations in western North America that allowed the ocean to flood in and form this shallow sea may have been caused by downwards flow in the mantle. This downwards flow was likely caused by oceanic crust that was subducted at the western margin of North America. That is, oceanic crust that went underneath the North American plate and into the mantle. Because this crust was part of the Farallon oceanic plate, it is often referred to as the Farallon slab.

As oceanic crust associated with the Farallon plate continued to sink into the mantle, it continued to cause changes in the elevation of North America. This drop in elevation likely decreased in size as the Farallon slab moved towards the eastern edge of North America, and deeper into the mantle.

Since Eocene time, or about 55 million years ago, dynamic topography associated with the Farallon slab is thought to have been in part responsible for lower elevations in the eastern United States. A wave cut escarpment called the Orangeburg Scarp is now located 50 to 100 miles inland from the coasts of Virginia, Georgia and the Carolinas. It formed at sea level and now lies up to 50 meters, or about 165 feet above the modern coast line. In fact, a good part of the southeastern US to the east of this escarpment contains marine sediments, and smooth topography as a record of its time underwater.

Differences in the elevation of the Orangeburg Scarp along its length suggest that rather than just going up and down, the Atlantic coast experienced a broad warping caused by mantle flow. The most recent phase of warping brought this area to modern elevations, as warm material moved into the upper mantle beneath the Atlantic coast. This warm material helped push the crust up to higher elevations, creating the southeastern US as we see it today.

This example also highlights an important part of dynamic topography: If you are already at really high or really low elevations, you might not notice it much. If you are near the coast, it can have a big impact as the sea starts to flood in and out due to changes in the mantle. Provided of course, you’re there for the millions to tens of millions of years it takes for the mantle to flow this way and that. That’s why geologists typically rely on the rock record to provide evidence for processes like dynamic topography. —Petr YakovlevThis episode was recorded at the studios of KBMF-LP 102.5 in beautiful Butte, Montana. KBMF is a local low-power community radio station with twin missions of social justice and education. Listen live at butteamericaradio.org.

Links:What is Dynamic Topography?Surface expressions of mantle dynamicsDynamic topography, eastern US

Show More

Rate

Join Podchaser to...

- Rate podcasts and episodes

- Follow podcasts and creators

- Create podcast and episode lists

- & much more

Episode Tags

Do you host or manage this podcast?

Claim and edit this page to your liking.

,Claim and edit this page to your liking.

Unlock more with Podchaser Pro

- Audience Insights

- Contact Information

- Demographics

- Charts

- Sponsor History

- and More!

- Account

- Register

- Log In

- Find Friends

- Resources

- Help Center

- Blog

- API

Podchaser is the ultimate destination for podcast data, search, and discovery. Learn More

- © 2024 Podchaser, Inc.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Contact Us